by Leo W. Banks

Tucson Weekly

January 14, 2010

Original article

Cross-border drug smuggling is a nasty trade that generates much misery, and that extends to the horses used to carry loads across Southern Arizona’s remotest lands.

When these animals are too worn out to work anymore, the traffickers often cut them loose to fend for themselves. The lucky ones are found alive.

But lucky is a relative term.

By the time traffickers abandon them, smuggler horses are often painfully thin, weak and badly used up. The heavy loads they’re forced to carry rub the hair—and sometimes the flesh—from underneath their front legs, their bellies and the area along the backbone.

Many have oozing sores and serious infections. These can be caused by rope or wire digging into the animal’s flesh, saddles without protective blankets underneath, or cinches pulled too tight.

One smuggler horse, stolen on the Tohono O’odham reservation and found in the Ironwood Forest National Monument northwest of Tucson, had the point of a two-by-four, part of a makeshift saddle, digging through its skin and into its kidney.

“I’ve seen animals with sores open plumb down to the bone,” says Rudy Acevedo, who works the Nogales area as a livestock officer for Arizona Department of Agriculture. “They have absolutely no mercy on these poor horses. They work them until they can’t go anymore.”

Judging by the number of abandoned smuggler horses reported to the state, the problem is significant.

State livestock officer Brad Cowan says that in the southeast corner of Arizona, including the area from the Tohono O’odham reservation to the New Mexico line, his agency “very easily handled 100-plus head of smuggler horses” in 2008.

“We started slower in 2009, at least until summer, then it picked up again,” says Cowan. “I’ve handled about 40 horses since June.”

The actual numbers might be higher, though, because some horses can’t be accounted for. These include strays taken in by individuals or those that die from exposure and attacks by predators.

Acevedo says he found four horses dead in open country last year, although he can’t say what caused their deaths.

“The only animals we know about are the ones reported to us,” says Dr. Phil Blair, Arizona’s assistant state veterinarian. “It makes you wonder how many others are out there we don’t know about.”

Not all horses found roaming the countryside had been smuggler horses. Some are turned loose by citizens no longer capable of caring for them—an acute problem now in the sagging economy. (See “Dead in the Desert,” Currents, Jan. 7.)

How can inspectors tell a horse was used for smuggling? In some cases, there’s no doubt—the Border Patrol comes upon smugglers in the act, and the traffickers scatter, leaving the drug-laden horses behind.

This happened in October along Duquesne Road in the Patagonia Mountains. A surprised smuggler abandoned a string of seven horses carrying 971 pounds of marijuana.

Acevedo inspected those horses and found them in good shape. “I think their smuggling careers had just begun,” he says.

In other situations, inspectors can make educated guesses based on several factors, in addition to the animal’s condition. Cowan says one good sign is if the horse carries a Mexican brand; another is the area in which it is found.

The corridors that attract the most foot traffic also draw horseback smugglers, and these include the San Rafael Valley and the Patagonia Mountains east of Nogales, the hills around Arivaca and west to Sasabe, and the Tohono O’odham reservation.

But Cowan says he’s found abandoned horses as far north as Stanfield, not far from Interstate 8. The smuggler had led the animal all the way across the reservation, finally turning it loose at least 80 miles north of the border.

“This horse had a Mexican brand, and I think it was just a throwaway,” he says. “They got to their destination and turned him loose.” As the two accompanying photos show, the animal had scars on its back, and was dehydrated and underfed: Its ribs and hipbones protruded.

By law, foreign strays must be turned over to the state Department of Agriculture, which then asks the U.S. Department of Agriculture to conduct blood tests. If the animal tests positive for certain diseases, which is unusual, it is put down. If the tests determine the animal is healthy and not a threat to infect American herds, it goes to public auction.

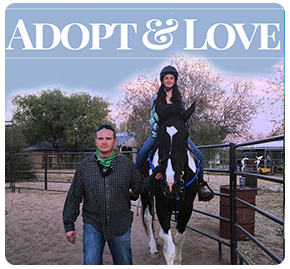

Stray animals in such poor condition that they cannot be auctioned are sometimes taken to one of several local rescue organizations. Karen Pomroy, who runs the Equine Voices Rescue and Sanctuary in Amado, has taken in 12 smuggler horses in the past year.

She says restoring these animals to health can take up to a year and cost thousands of dollars, after which she tries to find people to adopt them. But that can be hard, especially if the animal is lame.

“Most people want a horse they can ride,” says Pomroy. “If I can’t adopt a horse out, I’ll keep it here forever.”

Cowan says one of the worst cases he has seen was a horse he came across south of Three Points. It suffered from abscesses, hunger, dehydration and such leg weakness that it could no longer stand up.

He and another man had to pick up the animal by hand and put it into a trailer. After getting it into a pipe corral, the horse sat back with its butt against one of the rails to take the pressure off its legs.

“If you told me that, I’d call you a liar,” Cowan says. “But I saw it myself. That poor animal couldn’t even stand up. It’s just horrible what these smugglers do to them.”