ABUSED HORSES FREE AT LAST

by Carmen Duarte

Arizona Daily Star

July 9, 2010

The rehabilitation of drug smugglers can be a monumental task, especially when the offenders are biting, kicking beasts.

But volunteers are undeterred.

They take on the mares, stallions and thoroughbreds that once carried multimillion-dollar loads of illicit drugs through rugged canyons on down to parched desert.

These are horses that were at the mercy of drug runners – enslaved and worked nearly to death before being captured and taken to animal rescue organizations.

Others are still working the routes – far from deliverance.

Rudy Acevedo, an Arizona Department of Agriculture livestock officer, is among those saving these horses throughout Southern Arizona.

“These smugglers are using the horses over and over and over again until their backs, legs and bellies have open sores,” Acevedo said. “The drug smugglers are damn cruel to these animals. They run them into the ground and then just abandon them.”

About 75 horses each year are found abandoned in Southern Arizona and then turned over to the state Department of Agriculture, Acevedo said.

The animals are tested to make sure they are not carrying diseases before they are placed with one of three animal rescue groups in Southern Arizona for rehabilitation and adoption.

Those in better condition are taken to auction.

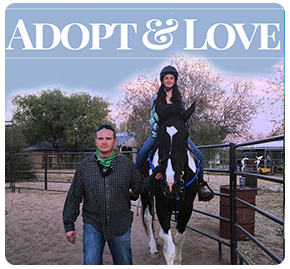

Lorilei Peters, owner of Desert Springs Equestrian Center at 9200 N. Ghost Ranch Trail in Marana, welcomed some of the horses after she was approached in 2008 for help by Karen Pomroy, president and founder of Equine Voices Rescue & Sanctuary in Amado.

Each operation takes in about 10 to 15 horses a year that were used to smuggle drugs. The horses are among up to 45 abandoned by owners each year that are cared for by the operations.

Volunteers, donations and sponsorships help Peters and Pomroy pay for care of the abandoned horses. The total costs for these animals is about $120,000 a year at each rescue center.

Helping the former drug-running horses in need is a calling for Peters.

“I remember Hope and Joy. Both had sores on their backs, hips and underneath around their legs,” Peters said.

“The sores were from the packs of drugs and the cinch that was on too tight. These horses are loaded with up to 400 pounds.

“They were both pregnant horses that were so emaciated we thought they had worms in their stomachs. They were a sack of bones, except for their bellies that kept growing,” Peters recalled. “The foals … were born without any problems and were adopted.”

Hope and Joy remain at the ranch in training to become riding horses and await adoption, Peters said.

It can take months to more than a year for their physical wounds to heal, and the horses also must heal psychologically, said Elisa Hambright, ranch manager at Desert Springs.

She massages the horses to get them familiar with a pleasing human touch.

“They don’t trust humans,” said Hambright, who oversees their daily care. “They have been mistreated and they remember. They turn their butt toward you and kick. They fan their ears toward the back of their head, which can be a sign of anger. A few bite.

“Trainers and I spend time with them. We show them they will not be mistreated and that we are here to help them,” she said.

“It is a slow process.”