Tucson Citizen

letters@tucsoncitizen.com

EDITOR’S NOTE: Controversy continues over Premarin mares – whose urine during pregnancy is needed to manufacture that once-popular drug used in treating symptoms of menopause. The fate of these mares and their foals has been the focus of not only the horse farmers, but also many animal welfare groups.

PRO: Strict codes followed by equine ranchers in U.S., Canada

CON: No place to go, unwanted feed-horse-slaughter industry

PRO: Strict codes followed by equine ranchers in U.S., Canada

NORM LUBA

Billie Stanton’s Aug. 7 column (“Hormones hurt women, horses”) contained misinformation about the equine ranching industry.

Although it was an opinion piece, uninformed opinions are a disservice to readers of the Tucson Citizen.

I am director of the North American Equine Ranching Information Council, an association of 72 family equine ranchers in the United States and Canada.

Our ranchers adhere to a science-based code of practice, which sets requirements for the proper care and humane treatment of horses, including climate-controlled barns, large stalls that permit horses to move around and lie down, regular turnout, nutritionally balanced diets and automatic watering systems.

Veterinary care on our members’ ranches exceeds the standard for other sectors of the equine industry.

The American Veterinary Medical Association reported recently, “Forty-five percent of U.S. household-owned horses did not receive a visit from a veterinarian.”

By contrast, 100 percent of horses on our members’ ranches have mandatory veterinary examinations at least twice per year.

Our ranches have been inspected by experts from the American Association of Equine Practitioners, Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, International League for the Protection of Horses and British Equine Veterinary Association, as well as representatives from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the North Dakota Board of Animal Health and the Manitoba Ministry of Agriculture.

They found that the horses are well cared for and that ranchers work hard to ensure the health, welfare and suitable placement of their horses.

Our ranchers are contractually obligated to sell their horses to good homes in productive markets, where the horses will be developed for competition and show ring, trail riding, police horse programs, and farm and ranch activities.

To ensure appropriate placement, we work with the independent Equine Placement Fund, which has funded transportation and health checks to successfully place more than 23,000 horses into these productive markets in 48 states and several Canadian provinces.

Our association’s ranchers were horse breeders long before they became involved in Premarin mare ranching.

Their family owned and operated farms that have quality breeding and husbandry programs, producing prize-winning paint horses, quarter horses, appaloosas, Belgians, Percherons and Clydesdales.

For example, Blueboy Dreamer, a 1998 registered quarter horse gelding that was foaled on an equine ranch in Brandon, Manitoba, has won the All-American Quarter Horse Congress numerous times, was the 2004 and 2006 High Point Trail competition horse, is a reserve world champion and has been the high point Canadian bred quarter horse every year since 2003.

Blueboy Dreamer is just one example of the quality of horses foaled on equine ranches.

Horses from our members’ ranches are in demand for various disciplines throughout North America.

These horses account for less than 1 percent of the Canadian horse population.

Just because a local “rescue” group buys and resells horses from Canada does not mean the horses were bred within the equine ranching industry.

I have presented facts that are reported and verified by some of the world’s leading veterinary and equine welfare organizations.

I hope readers will recognize the high standards that our association represents.

Norm Luba, executive director of NAERIC, is a lifelong horseman with degrees in animal science and more than 25 years in academia and industry, specifically horse management.

CON: No place to go, unwanted feed horse-slaughter industry

AUDREY CAPRIO

In an oversaturated market, it isn’t easy to place hundreds of unwanted horses born each year.

But the horses keep coming from ranches that once were contracted by the enormous Wyeth pharmaceutical company.

Equine Voices and other rescue groups are making every effort to help ranchers place these animals safely.

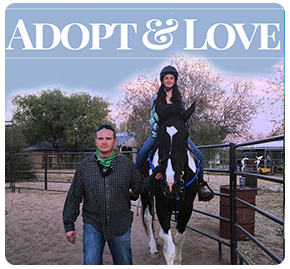

In early October, for example, Equine Voices plans to pick up five pregnant mares and five foals to adopt out or keep at our sanctuary between Green Valley and Tubac.

Such horses represent a long and controversial history, begun when Wyeth discovered in the 1940s that pregnant mares’ urine could be used to relieve symptoms of menopause.

The company soon began contracting with hundreds of U.S. and Canadian farmers to impregnate mares and harvest urine for production of its drug Premarin.

An estimated 422 farms soon had mares giving birth to about 40,000 unwanted foals each year.

Meanwhile, 22 million women in the U.S. were taking Premarin.

But when animal advocates starting seeing such horses sold at auction for slaughter, cries of outrage ensued.

In the mid-1990s, Helen Meredith of United Pegasus Foundation reported seeing hundreds upon hundreds of terrified foals, 3 to 6 months old, slammed into cattle carriers for transport to meatpackers’ feedlots.

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals soon published a brochure, “Premarin Exposed.”

ASPCA’s then-President Roger Caras wrote, “The abuse of horses in the production of Premarin is a total denial of our own history and our debt to the horse and the role this animal played in the exploration, conquest and utilization of our planet. What we are doing is unthinkable and unforgivable.”

A research study by the Canadian Veterinary Journal reported that 22 percent of foals born on PMU farms in western Manitoba between April 18 and May 31, 1994, had died of starvation, exposure or both.

In 1995, amid continued negative reports, PMU farms organized tours.

Still, both the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the World Society for the Protection of Animals made unfavorable reports.

So PMU farmers offered a second round of tours, excluding their critics.

Instead, they welcomed the American Association of Equine Practitioners and the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, considered by many to be little more than stakeholders in the PMU industry.

It came as no surprise when the resulting report proclaimed all was well.

Then in 2002, a Women’s Health Initiative study linked long-term use of Premarin and Prempro to increased risks of heart attack, stroke, dementia and breast cancer.

The effect was cataclysmic. Drug sales declined drastically, and Wyeth sharply cut its contracts with PMU farmers.

Over two years, an estimated 422 contracts were reduced to the 73 still operating in Canada.

This devastated the Canadian agricultural economy and led to about 20,000 pregnant mares, foals and stallions being sent to slaughter in early 2003.

The Humane Society of the United States and other groups implored Wyeth to help these farmers and their horses.

Wyeth responded by creating its Equine Placement Fund, to which it has contributed $6.75 million.

The fund requires all PMU horses to be sold individually to “productive markets,” via small auctions or sales organized by the North American Equine Ranching Information Council, which represents the Premarin mare farmers.

But the fate of the horses that are no longer useful is in doubt.

For example, Section 4.5 of NAERIC’s Code of Practice says: “No PMU operator shall dispose of a horse of any age, which is destined for slaughter, if is has been treated with medication, until such time as the withdrawal time has elapsed.

“The withdrawal time will either be as provided on the medication label or will be stipulated by the attending veterinarian.”

The council’s code also calls for safe construction of stalls for mares on the “pee lines.”

But the mandated width is a mere 3 1/2 feet for horses weighing less than 900 pounds and 5 feet for those exceeding 1,700 pounds.

A typical stall at a boarding facility is 12 by 12 feet, more than double the PMU mare’s stall size. And with a urine collection cup attached, how can PMU mares move around?

Equus Editorial reports the PMU industry has “contributed to widespread overbreeding that perpetuates the unwanted horse population that feeds the horse-slaughter industry that delivers horsemeat to markets abroad.

“The industry also drives the need for horse welfare legislation and rescue operations in a movement sweeping across North America.

“The ‘unwanted horse’ dilemma is huge, and it appears Wyeth will go down in history as one of the biggest contributors to it.”

Rescue groups are working to ameliorate this tragedy by helping former PMU farmers place horses rather than sending them to slaughter.

As for the human toll Premarin may have exacted, that concern is being addressed in the courts.

“In 2007, studies linked a drop in breast cancer rates with the reduced use of PMU drugs,” United Animal Nations reports.

“Six lawsuits have gone to trial alleging that Premarin or Prempro caused illness, and 5,000 lawsuits are pending.

“Yet Wyeth, the manufac- turer of Premarin, continues to market lower-dose versions of the drugs aggressively.”

Audrey Caprio is the adoption coordinator for Equine Voices Rescue & Sanctuary in southern Arizona.